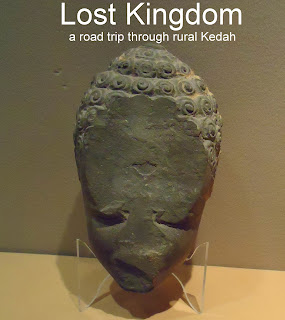

Lost Kingdom - A road trip through rural Kedah

The landscape of coastal Kedah is unerringly flat; a fluid place existing at the juncture of land and sky and sea, a place where the earth is more liquid than soil and stretches out in every direction until it is lost in the not-so-distant horizon’s humid haze. This is one of Malaysia’s main rice growing regions, where the high water table spirit-levels the landscape flat.

Alor Star, the principal town of Kedah, is easily passed through. Like every other town in Kedah it is a sleepy uneventful place.

Alor Star, the principal town of Kedah, is easily passed through. Like every other town in Kedah it is a sleepy uneventful place.

The K1 cuts a narrow two-laned straight line south across the sunlit landscape like an exercise in perspective, the vanishing point blurred by the hot and shimmering air. Traffic was light. My car moved over the tabletop flatness of this water-world where cauliflower cumulous clouds are reflected in the perfect mirrors of canals and flooded fields. The dark mud of newly ploughed padi fields shone and sparkled wetly under the sun. Other fields were filled with the vibrant green of newly risen shoots of rice. In places plots held older golden plants, almost harvest ripe.

The road was punctuated with villages, like sun-faded beads along a thread; villages with simple, but poetic names - Kampong Bahagia - the village of happiness, or Kampong Pisang - Banana Village, where white water-lilies grew in a small abandoned padi plot, and the intriguingly named Kota Sarang Semut - Ant’s Nest City.

Two shimmering white dots in the distance condensed and coalesced, solidifying to form a pair of cycling schoolboys in white shirts. They had schoolbags strapped to their backs and traditional black cylindrical songkok on their heads. The K1 could be a perfect road for cycling. Certainly no struggling uphill. For a moment I envied the schoolboys. On a bicycle you are immersed in the landscape, by immediacy and participation. Locked inside a car everything is filtered by a screen. My air was filtered too, but even with the air-conditioning the sunlight through the windscreen made me still feel uncomfortably hot. I clicked the switch up a notch. Thinking of potential heatstroke I decided I didn’t envy the cycling schoolboys all that much.

Further south, far in the distance, the Gunung Jerai loomed. The misty grey haze blurred the mountain to near invisibility, but as the kilometres passed its mass became darker and bigger, its outline more defined. Though I couldn’t see the sea I knew that it was very close. For millennia seafarers have used the Gunung Jerai as a landmark when navigating the Malacca Straits.

At Sungai Limau Dalam old men sat sipping cold iced drinks. They huddled together under the battered, rusted awning that provided them with a little shade, smoking home-made cigarettes rolled in hand-cut sections of nipah palm. Further on, another sun-bleached village that looked almost abandoned, was just a simple street of wooden shop-houses with weathered flaking paint and faded Chinese names.

For a few kilometres twin lines of neatly spaced trees bordered the roadside, casting evenly spaced patches of shade and light and shade and light and shade and light. Hand-painted signs at roadside stalls advertised Nira Nipah, a naturally sweet drink made from the tapped sap of the flowers of the ubiquitous Nipah palm. Occasionally padi-fields gave way and made room for small mango orchards. Almost every house had its own stand of sugarcane.

A huge grey windowless concrete bunker rose up in incongruous contrast to bucolic fluorescent green of the surrounding padi-fields. Every few kilometres I saw another one of these eyesores. Some were the equivalent of three or four storeys high, disproportionately bigger, and more solidly built than any of the modest kampong houses that I passed. The walls were blank except for rows of small round openings, that appeared to be made from evenly spaced sections of four-inch diameter pipe.

In Malaysia these ugly buildings are called ‘Swiftlet Motels’ - an ironic eponym for bird’s nest farms. Strategically placed loudspeakers broadcast strident chirping recordings of nesting swiftlets’ calls to tempt the birds to nest in these concrete condominiums. Hundred of birds flitted through the air above the surrounding fields and canals, feeding on the plentiful supply of insects, swooping low over the gleaming water, lightly rippling the surface as they scooped beakfuls to drink.

Swiftlets’ natural homes are found in limestone caves, where strands of their saliva are woven into nests. These nests are considered a delicacy by Chinese and give a gelatinous texture to bird’s nest soup. A kilogramme of bird’s nest can sell for as much as two thousand U.S. dollars. The rarer ‘red nests’, or ‘blood nests’, can fetch five times that amount. For anyone with the capital to build a bird’s nest bunker the return on investment is potentially far higher than can be made from growing rice. And the swiftlets do the work.

After Dulang Besar, several small hills were visible a few kilometres to the west. In fact they were tiny wooded islands that sat just off the hidden shore.

The unerring straight line of the K1 ends at the tiny T-junction town of Yan, which sits nestled at the foot of the Gunung Jerai. At an altitude of just over 1200 metres the Gunung Jerai (sometimes known as Kedah Peak) is northern Malaysia’s highest summit. From Yan onwards the road skirts the mountain’s base.

In the microclimate of the mountain the dense vegetation sought to reclaim old wooden homes. Some were obviously abandoned and long beyond repair, others merely in an advanced state of dilapidation. Cheap polyester curtains and neat piles of brown coconut husks showed that, despite walls of weather-worn planks listing at alarming angles, these homes were still inhabited. A few houses were well maintained and had been painted in bright colours of yellow and orange, but most commonly faithful hues of Islamic green. Some houses sprouted concrete extensions that, though obviously functional and practical, did little to complement the traditional wooden architecture. The sea was visible in glimpses between the trees with more small wooded islands just off the coast near Sungai Udang (Shrimp River), and a place with the musically playful name of Titti Bakong. At Tanjung Jaga silhouettes of men stood in small fishing boats, scissoring their arms and playing out their lines.

Drooping powerlines cast undulating shadows on the grey asphalt – a portent of the next few kilometres of road, which rose and fell and twisted like a roller coaster. Huge Petai trees shaded the road and dangling in inaccessible bunches were their leguminous outsized pods. Petai is said to be good for cleansing kidneys, but their pronounced pungent taste, which to my mind is not dissimilar to garlic, has a tendency to leave an overpowering odour on the body and the breath that lingers for many days.

Potted bougainvilleas stood in front of almost every home, the bracts in colourful bloom in psychedelic tones of hot pink, magenta, orange, purples and vivid crimson. A quarry in the mountainside had taken an ugly giant-sized bite. At Singkir Dimat a corpulent woman sat reading a newspaper in the roadside shade with a huge transparent plastic tub of iced green sugarcane juice by her side. The ice almost tempted me to stop, but cane juice and I don’t get on so well. It starts out nicely, then I tend to talk too much, and too fast, and can’t quite seem to stop – useful at times for a story-teller, but after the high comes the inevitable hypoglycaemic crash and I need to find a corner to crawl away and hide.

The road winds through Kampung Simpang Tiga Pasir (Three Sands Junction) and on to the tiny town of Merbok, which has been one of my goals on this road trip. It’s not Merbok itself that interests me however, but the ancient ruins of the Lembah Bujang, (or Bujang Valley) nearby. I leave the K1 and follow the K631 as it climbs uphill past orchards and wooden beehives. In five years in Malaysia these are the first beehives I have seen, which surprises me in a country full of flowers and whose inhabitants have phenomenally sweet-tooths. That said, wild (and increasingly adulterated) honey can be bought at roadside shacks in the Cameron Highlands from the Orang Asli - Malaysia’s original inhabitants. I look for a place to buy some honey, but there doesn’t seem to be one.

A woman in a uniform waves me through a raised barrier and I leave the car on the near-empty car-park in the only patch of shade. The midday heat is oppressive and my shirt sticks to my skin. The visitor’s book at the site’s museum shows that I am the first foreign visitor in many days, and apart from one Tamil-Malaysian family who stroll around for ten minutes, I have the ruins of the Bujang Valley all to myself. The museum is mercifully air-conditioned and I’m surprised that there is no entry charge. Malaysia is very good like that – access to most historic, cultural and natural sites is free, though occasionally you might have to pay a nominal sum for parking.

The archaeological exploration of the Bugang Valley has been intermittently ongoing since as early as the 1840s and excavations have revealed that there were once extensive Hindu and Buddhist settlements in the immediate region.

But in early 2009 the discovery of a vast new Bujang Valley site, unearthed in a palm-oil plantation in nearby Sungai Batu, shed new light on the true extent of the ancient civilization that grew around the foot of the Gunung Jerai. It seems to have covered over a thousand square kilometres, though it was previously assumed to be less than half that size. Among the more recent finds is an unusual clay-brick platform quite unlike anything else ever discovered in the region, and though its true function is unknown, it is assumed to have had some sort of ritualistic function.

In total almost 100 new locations have been identified, and though less than twenty have been excavated to date, they reveal evidence of an extensive iron smelting industry in the region. Brick riverside quays, combined with the proximity to the sea, suggest a potentially vast distribution network through India and China, which were the dominant powers at the time and controlled the maritime trading routes of the Malacca Straits.

Initially the ruins at the Bujang Valley were dated as being from between the 8th and 13th centuries, which would make them roughly contemporary to Borobudur in Indonesia (8th century) and Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, (which dates from the 11th century). Until recently Vietnam boasted South East Asia’s oldest set of ruins - the Siva-Bhadresvara Temple in My Son (4th century AD). However, these new sites in Sungai Batu have been dated to between the 1st and 3rd centuries, and thus the most ancient man-made structures in the entire region, effectively re-writing the history books by making the Bujang Valley home to what was possibly South East Asia’s oldest civilization.

Abstract modern sculptures, that look something like giant chess pieces, stand in front of the museum. Try as I might I couldn’t interpret their significance. They certainly seem to bear no correlation with any of the artefacts inside, or make any attempt to echo Hindu or Buddhist themes. As if to further reinforce this impression a large sign outside the museum is written in Jawi script.

Jawi is based on Persian script and resembles modern Arabic and though it has largely fallen into disuse is still occasionally used to write the Malay language in some of Malaysia’s more conservative states - a heading under which Kedah can be firmly placed. In some places in Malaysia Jawi script can still be seen on old shop fronts, usually hand-painted and rather faded. Nowadays the vast majority of people use rumi, which has nothing to do with the mystical Persian poet, but is perhaps a deformation of ‘Roman’ as it refers to the standard Latin alphabet.

The museum exhibits potsherds, metal tools and stone carvings of Hindu gods, including Ganesha, Shiva and Durga, most of which have been remarkably well preserved. A slightly smaller than life-sized Buddha’s head, recognizable by the inimitable hairstyle, has been literally defaced, with just a smooth flat plane of greenish stone where the features must once have been. Whether this happened accidentally or otherwise is left to the visitor’s imagination, though it does have the look of having been deliberately chiselled away.

All the descriptions are written in Malay, which is natural, as it is the national language of Malaysia, but this left me at a distinct disadvantage. My meagre grasp of the Malay language may be sufficient for the night market, but it certainly isn’t up to interpreting detailed descriptions of ancient archaeological artefacts. The few notices that are written in English are only poorly and partially translated. I wanted to buy a guide book to help me better understand the site and its remains, but there was no documentation available in any other language than Malay. *

Malaysia is a pluri-cultural and multilingual country, but is often ambiguous and ambivalent about how it embraces that. Schooling is split on ethic and linguistic lines and anyone who wants their children to learn to read and write in Chinese or Tamil can do so. Of course Malay is still studied as a separate language in these ‘vernacular schools.’ When it comes to second-level schooling almost all children study the same curriculum in the same language, namely Malay.

A not dissimilar system exists in my native Ireland, which is technically a bilingual country. Also Belgium, where I lived for many years, has schooling in French, Dutch and German - the country’s three official languages. Later I lived close to the Spanish Basque Country where bilingualism is part of the cultural heritage. In the case of all these places the individual languages are often used side by side, which can admittedly make for some outsized and confusing road-signs, but in the hypothetical example of a museum exhibit, allows everyone to read the descriptions in their mother tongue.

Malaysia is not like that. Assuming, perhaps quite wrongly, that an archaeological site of Buddhist and Hindu remains might be of more interest to Malaysia’s present day Buddhists and Hindus, rather than it’s Muslim population, it might be useful, informative and educational to have descriptions written in Chinese and Tamil too. But as stated above - all Malaysians learn to read and write Malay in school, just as I learned to read and write in Irish in school. But if it comes to reading anything even the slightest bit complicated in the first national language of my own country I would always opt to read the translation into my mother tongue.

It is unfortunate that any information on what is one of South East Asia’s most important historical sites is essentially rendered inaccessible to the vast majority of international visitors. But as noted above, not many foreign visitors seem to make it this far anyway. The site is not particularly well known and in fact I was startled to learn that the vast majority of Malaysians to whom I spoke about my little road trip had never even heard of the Bujang Valley, never mind ever having visited it themselves.

Though it would be unfair to compare the ruins at the Bunjang Valley to Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, because there truly is no comparison, the extent of the touristic and economic development around Siem Reap hints that the Bujang Valley’s past might be something worth exploiting and developing for the future. However my visit left me with the impression that Malaysia is somehow vaguely embarrassed by its rich and diverse past and would rather downplay the cultural and historical significance of the Bujang Valley rather than celebrate and exploit it for what it is.

Stepping out of the air-conditioned climate of the little museum I proceeded to wander around the ruins, some of which are remarkably well preserved, though I suspect that they may have been partially rebuilt. Again the dearth of available information left me feeling a little frustrated.

The ruins are mainly built in laterite – a magical material, half-clay, half-rock, that exists almost uniquely in the tropics. Laterite is iron-rich and rusty-red in colour. It can be cut in blocks or bricks which solidify when exposed to the air. Those familiar with the older parts of Malacca will have seen laterite slabs and blocks employed in the old city walls and fortifications. It is an extremely hard-wearing material as is proven by the fact that the ruins in the Bujang Valley have remained preserved for more than a millennia and a half.

As I strolled around the remains of what were possibly old temples, again I couldn’t help feeling that the whole significance of the Bujang Valley was being deliberately underplayed. Indeed there are reasons to believe that this may actually be the case.

Unfortunately some reductionists would have Malaysian history begin in the 12th century AD with the introduction of Islam by traders from India. By the 15th and 16th centuries Islam had become the chosen faith of the majority of the Malay people. Since independence from Great Britain in 1957 faith is no longer a choice for Malays, and from that point onward, the Malay identity has been inextricably founded on being Muslim, whereas in neighbouring Indonesia, Thailand or the Philippines there are ethnic Malays who are Buddhists, Hindus, Christians and even animist – but these are uncomfortable truths - and any discussion of ethnicity or religion in Malaysia is a potential minefield, which is a pity since they are two of the most fascinating aspects of the country.

Though the Malaysian constitution enshrines Islam as the ‘religion of the Federation,’ more than one third of the country’s population are non-Muslim, and there is still an ongoing debate as to whether Malaysia is a secular state or an Islamic state. Taking into consideration that the majority of the non-Muslim segment of modern Malaysia’s population are also Hindu’s and Buddhists, the truth about the Bujang Valley has the power to raise some awkward truths. To expose and preserve a huge body of archaeological evidence that clearly reveals that the present-day Malay’s ancestors were Hindus and Buddhists undermines the very definition of what it means to be Malay. Being caught on the dichotomy of preserving the past, and admitting that to be Malay didn’t always mean to be Muslim, seems to have led to the site being kept under wraps, or at the very least poorly marketed as a tourism product.

There are persistent rumours (which seem to originate from students working on the archaeological digs) that many of the artefacts found have been deliberately destroyed, with stories of statues being defaced and smashed by pious individuals eager to brush over the uncomfortable truth of Malaysia’s Hindu and Buddhist past. There are also the inevitable tales of prize pieces being sold on the black market to private collectors, which has often been an unspoken element of archaeological excavations anywhere.

In truth, no one really knows how much, or what exactly has been unearthed during more than one hundred and sixty years of excavations in the area. Legends tell of caves filled with golden chariots and jewels. But if such treasures have been found none of them are on display. Given the extent and timescale of archaeological investigation in the area the smattering of artefacts shown at the site are just the tip of the iceberg (or cultural landmine, as the case may be). Certainly, some items went to pre-independence Singapore, while others are, or rather were, displayed in the Museum Negara in Kuala Lumpur. In recent years many magnificent items have mysteriously disappeared from Kuala Lumpur’s national museum, including various idols and a legendary three-meter-tall throne said to have belonged to Raja Bersiong.

Long before Bram Stoker wrote Dracula, Malaysia already had its own vampire, complete with fangs and a taste for blood. Raja Bersiong, whose real name was Ong Maha Perita Doria, was the infamous ruler of the Kingdom of Langkasuka which according to some was situated in present-day Kedah, around or near the foot of the Gunung Jerai, not very far at all from the Bujang Valley.

It all started out innocently enough, as these things often do. Grumpy because he hadn’t eaten, the Raja scolded his cook for taking too long to serve his meal. In his haste to prepare the food the cook cut his finger with a knife and a few drops of blood fell into the Raja’s dish. Not wishing to endure his ruler’s displeasure, any more than he already had, the cook served the food as it was. The Raja enjoyed the food so much that he insisted that the cook reveal his new secret ingredient. The cook, fearful of the Raja’s wrath, decided to tell the truth, and from that day on the Raja’s food was seasoned with human blood.

Over time Raja Bersiong’s hunger for human blood increased - as did the length of his incisor teeth. Villagers were captured and held prisoner in the nearby Gua Penjara (Prison Cave) and their blood was served to the increasingly blood-thirsty king. The remaining villagers feared that they would be captured too, so they plotted together and planned an attack, then stormed the Raja’s palace intent on regicide. The Raja, realizing the danger he was in, fled into the nearby forests at the foot of the Gunung Jerai. The villagers hunted for their erstwhile ruler in vain, but he repeatedly avoided capture.

There is a traditional Malaysian solution when all else fails – which was as valid back then, as it is today - find a bomoh. A bomoh was found. He cast a spell on Raja Bersiong and transformed the former ruler of the kingdom into a humble boar.

The morals of this story are: (a) even if you are in a hurry to cook food always be careful with sharp knives and (b) never reveal your secret ingredients.

The Bujang valley is a quiet, peaceful place with lots of trees and it is difficult to picture that this was once the site of a vast civilization.

Chinese records dating from the 4th century mention the kingdom of Langkasuka and say that it was founded in the 1st century. Though there don’t seem to be any references that explicitly and conclusively confirm that the civilization that existed around the Bujang Valley was part of the ancient kingdom of Langkasuka no other ruins that that fit the same time scale have been found and the details seem to fit with the archaeological evidence and recent discoveries at Sungai Batu.

Stories from a wandering Chinese Buddhist monk tell how he met three Chinese monks in a great walled capital of Langkasuka (Lang-chia-su). By the 12th Langkasuka had come under the control of the Hindu Srivijaya Empire, but later, around the 15th century it became part of the Pattani Kingdom.

There is some debate over the exact etymology of the name 'Langkasuka.' The most commonly given version is that it comes from Sanskrit langka meaning 'land of glory' and asoka referring to Emperor Ashoka, who was instrumental in the spread of Buddhism throughout most of Northern India and much of South East Asia. Others say that langka refers to the jackfruit tree, (known as nangka in Malay, or langka in Tagalog) that was introduced from Southern India to South East Asia and is still frequently grown in the region. In any case the kingdom is documented repeatedly through history and then simply vanished. The records show that Langkasuka traded not only with India and China, but possibly owed its origins to ancient Rome.

The Kedah annals tell that the Kingdom of Langaksuka was founded by Merong Mahawangsa, a Hindu ruler and trader who is said to have been a descendant of Alexander the Great and lived in Rome. He set out on a trading mission to China but ran into trouble when he and his fleet were attacked by a giant eagle in the Malacca Straits. They came ashore at the foot of the Gunung Jerai and Merong Mahawangsa proceeded to establish a new kingdom there. Eventually he returned for Rome, leaving Langkasuka in his son’s hands. Certain versions of the legend say that he died on his return journey. Whether this death was in anyway related to giant eagles is not mentioned.

Overall the park around the Bujang Valley ruins is well maintained with almost no litter in sight, which might be attributable to the fact that there were no visitors. There is a trail to the top of the mountain, but the intense heat, the whining hungry mosquitoes and a rumbling stomach made me disinclined to undertake the climb.

I drove back downhill past the beehives. Clouds of cotton from a recently felled Kapok tree drifted across the road. A little further I passed a Hindu Temple and a Tamil school and spotted a sign for a recreational zone. I took a detour up a peaceful stretch of road following a little river that had its source somewhere on the slopes of the Gunung Jerai. The water level was low, so it was hardly more than a stream. A skittish chameleon darted across the road. Stands of tapioca and orchards where dappled sunlight filtered through mango leaves, gave way to a forest of towering trees with tremendous buttress roots.

I stopped the car a few times, stepping out to touch the rugged bark of the giant trees while the whine of unseen insects filled the air. Further upstream I found a spot where the water flowed faster and deeper. Two young Malay women sat bathing fully clothed in the deepest part of the stream, chatting quietly, their words mingling with the bubbling rush of water over and around the rocks. I kept a respectful distance and waded up to my knees letting the river cool my overheated blood while standing in the shade. Birds sang and a chattering kingfisher darted electric blue over the water and perched on a nearby rock. The water was perfectly clear and the riverbed was decorated with chunks of shining silica that twinkled and gleamed depending on the angle that I stood.

The river was also filled with plastic. I fished out pink plastic bags, bottles, cups, tubs, straws and string. On the bank the smooth rounded rocks on the river’s edge were discoloured from the noxious soot of a half-burned, congealed mess of Styrofoam takeaway boxes and plastic mineral water bottles. I tried to use a stick to prise it away from the rock, but it was molten fast. The two girls watched my antics and giggled between themselves.

If there’s something I’ve learned in five years in Malaysia it’s that anywhere that people can conceivably throw rubbish, they invariably will. There is a trail that leads through a tract of virgin rainforest close to where I live. I’ve taken to carrying an empty rubbish bag with me every time I hike the trail. I can easily fill it with discarded plastic bottles. A local told me recently that I shouldn’t pick up the bottles. I asked him why and he replied that bomohs use them to contain cast out spirits and that if I took a cursed bottle then evil spirits would follow me home. When I asked why a bomoh would go to all the trouble of hiking into the rainforest just to throw away plastic bottles instead of just putting them in the rubbish bin he had no answer.

I added the river-washed plastic to the pile beside the overflowing rubbish bins. Some optimist had nailed a laminated plastic notice to a tree. It said 'Recycle, Reduce, Reuse'. I dreaded to think what the place would look like a week later during the school holidays. Despite the nauseating smell from the rubbish bins my stomach rumbled, reminding me that I still hadn’t eaten yet. It was only a few kilometres further to Bedong, another planned halt on my route.

The floor of the five-foot-way shone polished by years of scuffing shuffling feet of shoppers, schoolchildren and sundry passersby. A late afternoon breeze announced that the oppressive heat of day would soon be replaced by the sultry humidity of night. The slats of a bamboo blind wavered in the breeze, casting parallel lines of sunlight and shade on the shining smooth cement. The sound of a metal spatula clanging against a sonorous steel wok echoed in the shaded arched passageway. The woman cooking had her back to me. She wore yellow rubber boots and stood with her feet apart in a broad stance as her arm and shoulder battled noisily with her pan. The acrid smell of hot chillies wafted through the air catching me in the throat. The woman turned her face clear from the harsh bite of the dish, leaning back and squinting like a smoker avoiding her own smoke. I saw that she was old and years in front of the flames had ravaged her pink blotched skin. In out-of-the-way places like this where western faces are seldom seen I’m often greeted by a double take or an impenetrable stare, but this woman greeted me with a wide smile and a coughing cackling laugh. I placed an open hand over my fist and brought my hands up to my heart, the woman smiled more, nodding deeply like a bow as she coughed and turned back to her wok again.

The kopitiam was half-full and curious eyes all turned towards me. I sat down at one of the empty round marble-topped tables on an aged wooden chair. Conversations resumed in an unknown Chinese tongue, but the three men at the table next to me kept looking my way. There was nothing threatening or intimidating in their attitudes - they were merely curious, with the open-faced expressions of uncomplicated men. I caught their eyes and nodded to them, dipping my head with a smile. They replied likewise in return, but with dropped eyelids and faint blushes, like small children unsure how to behave around strangers. A young man in a stained t-shirt that might once have been white hovered behind the drinks counter, eyeing me uncertainly as he half-hid behind a pyramid of cans of condensed milk. Another young man, a teenager still in school uniform in fact, entered the shop and made for the counter. A muttered exchange ensued and the schoolboy came to take my order.

“Drink you want what?” he asked.

I replied with one of the few phrases of Mandarin I know, learned specifically for times like this, and ordered a pot of tea.

“Hot tea,” I emphasized “Don’t want ice.”

The three men at the table beside me chuckled among themselves and encouraging smiles and thumbs were raised in appreciation for my valiant efforts. The words for ‘tea’ and ‘fork’ sound almost exactly the same in Mandarin, with just the subtlest variation in tone. It has taken me years of practice to get the pronunciation just right. In the past, despite my best efforts, I just drew blank stares, but today I was rewarded with a scalding pot of tea and a small plastic basin of boiling water with two tiny handleless cups inside. I used to burn my fingers on the cups, but when I deftly used a pair of chopsticks to extract the steaming cups my three neighbours gave another appreciative laugh.

“You long time Malaysia ‘ready,” affirmed a thin man with glasses. He looked young, but his thick shock of hair was already quite grey.

“Can speak good Mandarin.”

I shook my head and smiled.

“I only know how to ask for tea.”

I stood up and ordered a bowl of won-ton-mee from the old woman outside on the five-foot-way.

“What language are you speaking?” I asked the men when I sat back down back.

At first when I came to Malaysia I couldn’t tell Chinese dialects apart, but since then I’ve learned to distinguish between the music of Mandarin and Hokkien and two years living in a working class suburb of Kuala Lumpur have left me with a smattering of Cantonese. I knew they were speaking something else.

“Teochew. You dun know?” replied a chubbier man with three long hairs protruding from a dark mole on his chin.

I shook my head.

“Malay can or not?”

“Sedikit saja, sikit sahaja. Only a little.” This raised another laugh though it wasn’t meant to be funny.

“We also speak sedikit. Here everybody speak a little this, a little that.”

“Is it mostly Chinese in Bedong?”

“No lah. Here very mix. Got Chinese, got Indian, got Malay. One Malaysia lah, but like that awleddy before politician talk like that. We all just want happy together. Peaceful together. Only politician make problem. Then say ‘one Malaysia’. We just leave politic alone. We just want peaceful place.”

“But you changed state government not so long ago. How is it for Chinese with an Islamic party in control?”

The old lady placed a steaming bowl of noodles in front of me. The broth was flavoured with tongue-swelling MSG. Since I’ve been in Malaysia almost everyone I’ve met has reassured me that MSG is fine, but I have an occasional rash on my one of my legs that tells me otherwise. I could feel the back of my calf muscle tingle in anticipation as I slurped down the hot noodles.

“You mean PAS? You long time Malaysia lah. You know a lot. But I tell you, first time we dun know. What this fella like? We wait and see. But okay lah. No problem. Same same.”

“Not same,” said the third man, who hadn’t spoken yet. He chain-smoked and listened, while a wry smile played on his lips. “Not same. Better. This PAS, they very strong agains’ corruption. Too much corruption las’ time. Much better now. I think they win again. First Chinese a bit afraid, but we say wait and see. So we see lah, and it’s not so bad. Maybe better. Yes better.” He nodded and took another squint-eyed pull on his cigarette.

“You go see Chandi at Lembah Bujang. You want to know Malaysia, then know its history. Las’time only Hindu and Buddhis’ here. This place. Malaysia. Kedah. Now Islam, but still got Hindu and Buddhis’ lah. Cannot change the past. Cannot change the present. Maybe can change the future, but still got Hindu and Buddhis’. Got no more Hindu and Buddhis’ mean got no more one Malaysia. We the one who start this place an’ they still need us to do the work. Otherwise just got rice and fish, and like that cannot.”

I chatted with these amiable locals over another pot of tea.

“Why you come Bedong?” the grey-haired man asked.

“Do you know a Malaysian writer named K.S. Maniam?” I asked. “He used to live near Bedong when he was a boy. He wrote a book about it. I wanted to see the place.”

“A book about Bedong? Where got? Nothing to write book about here.”

“Really,” I said. “It’s called The Return.”

A muttered conversation based on my assertion that there really was ‘a book about Bedong’ ensued and I recognized the word Keling - a word that is commonly used by Chinese to refer to those of Indian heritage. It is quite an incendiary term and is increasingly taken as a grave insult, like using the N word to describe a person of African descent, though in my admittedly limited experience it is seldom meant that way. There was even an unsuccessful attempt to have the word removed from the dictionary. The K word is still common in place names throughout Malaysia, in fact I passed within a stone’s throw of Kampung Kedat Keling on my way to Merbok. There is a Kampung Tok Keling just outside Alor Star and Penang has at least three places called Kampung Keling as well as a mosque called Masjid Kapitan Keling.

Political correctness hasn’t fully filtered through all strata of Malaysian society – this is after all the country that until recently had a toothpaste (or ‘tooth medicine’) called ‘Darkie’ - with a cartoon image of a broadly smiling black man in a top hat as its logo. The iconic behatted black man still remains, though the K has now been replaced with L.

There is a scene early on in The Return where young Ravi (Maniam’s alter-ego) comes to Bedong with his father to buy his very first toothbrush and some ‘tooth medicine,’ since Miss Nancy, his new teacher in the English school in nearby Sungai Petani, disapproves of the traditional method of using a chewed twig and wood-ash to clean teeth. Afterwards father and son go to a coffee shop and sit at a marble-topped table. I wonder if this is the same coffee shop, maybe even the same marble-topped table where he sat.

To my mind K.S. Maniam is one of Malaysia’s most eloquent writers in the English language. The Return is an autobiographical description of his modest childhood in and around Bedong. A generation or so ago most Malaysians grew up with no running water or electricity. The majority of people’s lives have been utterly transformed over the intervening decades. Now many of their children and grandchildren live in an air-conditioned WiFi world.

That said there are still places like Bedong that have made few concessions to this rapid transformation and haven’t quite stepped into the 21st century yet. The town maintains a simple rural character and I suspect that if you peeled off the inevitable plastic and neon shop front signs you would find that very little has changed from Maniam’s description of the place.

*(While researching this essay I discovered that the Ministry of Information, Communications and Culture have produced a book in English entitled ‘Bujang Valley and Early Civilisations in Southeast Asia’. This book is a collection of papers presented at an international archaeological conference that took place in Kuala Lumpur in 2010 and discusses the context around the new findings at Sungai Batu, though it is difficult for ordinary members of the public to obtain. )

.JPG)

Hello from a Bedong boy! :) A friend pointed me to your blog, really love what you wrote. Will get me to read KS Maniam's book. I hope you love your stop in Bedong, would love to assist you if you are heading there again :) We grew up there, and as a kid most of what we are doing mainly after school in 70s were to ride to the Merbok waterfall for cool deep in the afternoon, (yeah a 15KM trip one way) and hear say about this Hindu Heritage, and till the 80s, I still have classmate whom the parent were Vege farming in the Bujang valley with occasion finding of loose gold jewellery piece, which he will sell it to local goldsmith and we will get treat of Coca Cola in School :)

ReplyDeleteSorry it took me so long to reply to this. Thank you for reading and for your fascinating comments. Best of luck.

Delete